We received two awards at the 12th International conference on Persuasive Technology. The best paper award went to Ana’s work on Subly, while Ligia, just on the very start of her PhD, won the best poster award. Well done girls!

We received two awards at the 12th International conference on Persuasive Technology. The best paper award went to Ana’s work on Subly, while Ligia, just on the very start of her PhD, won the best poster award. Well done girls!

With 50% of people spending over 6 h per day surfing the web, web browsers offer a promising platform for the delivery of behavior change interventions. One technique might be subliminal priming of behavioral concepts (e.g., walking). This paper presents Subly, an open-source plugin for Google’s Chrome browser that primes behavioral concepts through slight emphasis on words and phrases as people browse the Internet. Such priming interventions might be employed across several domains, such as breaking sedentary activity, promoting safe use of the Internet among minors, promoting civil discourse and breaking undesirable online habits such excessive use of social media. We present two studies with Subly: one that identifies the threshold of subliminal perception and one that demonstrates the efficacy of Subly in a picture-selection task. We conclude with opportunities and ethical considerations arising from the future use of Subly to achieve behavior change.

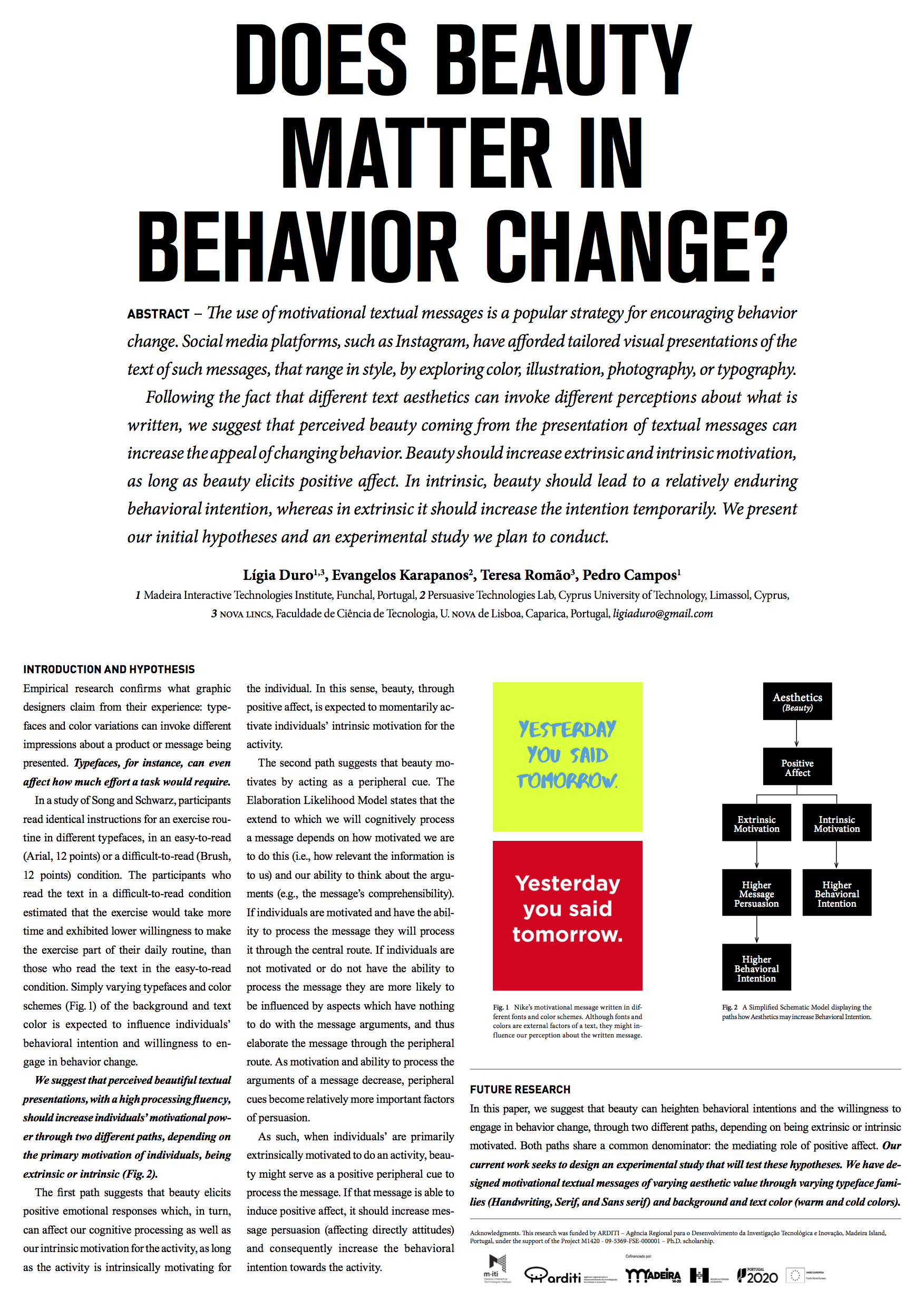

The use of motivational textual messages is a popular strategy for encouraging behavior change. Social media platforms, such as Instagram, have afforded tailored visual presentations of the text of such messages, that range in style, by exploring color, illustration, photography, or typography. Following the fact that different text aesthetics can invoke different perceptions about what is written, we suggest that perceived beauty coming from the presentation of textual messages can increase the appeal of changing behavior. Beauty should increase extrinsic and intrinsic motivation, as long as beauty elicits positive affect. In intrinsic, beauty should lead to a relatively enduring behavioral intention, whereas in extrinsic it should increase the intention temporarily. We present our initial hypotheses and an experimental study we plan to conduct.

| Duro, L., Karapanos, E.,Romão, T., Campos, P. (2017) Does Beauty Matter in Behavior Change?, In Adjunct Proceedings of Persuasive’17. |

We gave a talk in the WUD’16 Tallinn and WUD@ITMO events. The slides of the presentation are attached below.

Recent research reveals over 70% of the usage of physical activity trackers to be driven by glances – brief, 5-second sessions where individuals check ongoing activity levels with no further interaction. This raises a question as to how to best design glanceable behavioral feedback. We first set out to explore the design space of glanceable feedback in physical activity trackers, which resulted in 21 unique concepts and 6 design qualities: being abstract, integrating with existing activities, supporting comparisons to targets and norms, being actionable, having the capacity to lead to checking habits and to act as a proxy to further engagement. Second, we prototyped four of the concepts and deployed them in the wild to better understand how different types of glanceable behavioral feedback affect user engagement and physical activity. We found significant differences among the prototypes, all in all, highlighting the surprisingly strong effect glanceable feedback has on individuals’ behaviors.

| Gouveia, R., Pereira, F., Karapanos, E., Munson, S., Hassenzahl, M. (2016) Exploring the Design Space of Glanceable Feedback for Physical Activity Trackers, In Proceedings of Ubicomp’16. |

I intentionally chose a provocative title. Can we really design behaviour? Can technologies have such an influence on individuals’ behaviour that we can talk about “designing behaviour” through technology?

To a large extend, behaviour change technologies nowadays rest on the assumption that knowledge leads to behaviour change, an idea that is deeply rooted in the “quantified self” community. We assume, for instance, that making people aware of how much, when, and where, they walk (or don’t), will lead them to uncover patterns in their behaviours and take actions to increase their physical activity. Our research has revealed that this is not necessarily true, and that we often hold incorrect assumptions about how people use these technologies. For instance, our habito study, revealed that people rarely look back at their past performance data, and that only 30% of the users set their own walking goal.

Rather than thinking of such technologies as ones that enable deep reflection over one’s behavioural patterns, could we have more success if we focus on shaping the choice architecture at moments of decision making? Consider, for instance, the popular road sign stripes that are strategically positioned closer and closer together as we approach a steep curve, making us believe that we are over-speeding. Such a simple intervention has been found to decrease car accidents by 36%.

How could we transfer such approaches to the design of behaviour change technologies? I personally see two approaches. One is to infer when such critical moments of decision making happen – approaching the elevator, browsing through online food delivery options etc. A second is to provide persistent, glanceable feedback that keeps reminding people of their goal. Consider, for instance, that people glance at their smartwatches 80-150 times a day to check the time or incoming notifications. Might we leverage on this to present physical activity feedback at the periphery of their attention?

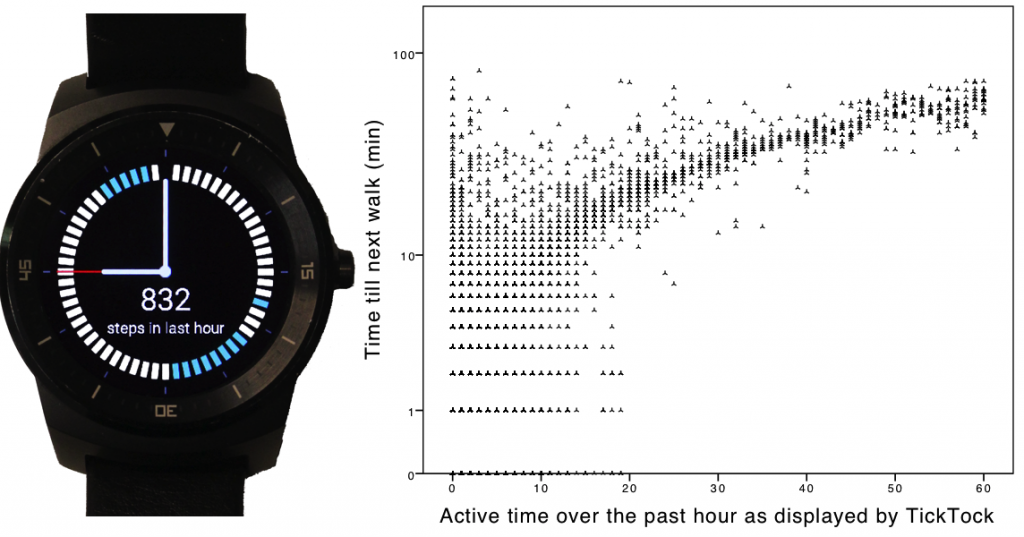

In our recent paper we explored just that. For the purpose of this blog article, I wanted to emphasize what we found with one of the prototypes we developed, TickTock.

Most activity trackers will tell you how much have you walked so far in the course of the day. This, of course, is routed in the idea that people set daily walking goals, and feedback serves to make them aware of their performance so they can meet their goal.

With TickTock, we tried to change the logic. TickTock will only tell you how active you were over the past hour. As a result, TickTock emphasises keeping a balance in your day, i.e. avoiding prolonged periods of sedentarism, which has been found to be a health risk factor independently of the amount of physical activity one performs over the course of a day.

What we found was rather astonishing, I think. I initially thought there must some error in the data. I asked Ruben to scrutinise the data collection script. He couldn’t find any error.

I turns out, TickTock had a profound impact on individual’s behaviours. We performed a linear regression analysis to predict the time people took till their next walk after checking the watch, based on the feedback they received, namely how active (o-60 mins) they were over the past hour. We found this single variable to account for 76% of the variance in the data! For every additional 10 min of physical activity that the participants saw they performed over the past hour, they would take an extra 9.5 min till their next walk. Participants who saw that they walked 10 or less min over the past hour had a 77% probability of starting a new walk in the next 5 min.

What do those findings suggest? First, that these technologies are far from neutral, they emphasise certain ways of living, and as designers, we should pay close attention to the assumptions embedded in our designs and to align feedback with the goal we want to achieve. Second, they highlight they surprising impact glanceable feedback has on individuals behaviours. The habito study highlighted that the dominant mode of use of physical activity trackers is glancing and it serves to support self-regulation of immediate behaviour. This study further demonstrated the power of glanceable feedback in shaping individual’s behaviours.

| Gouveia, R., Pereira, F., Karapanos, E., Munson, S., Hassenzahl, M. (2016) Exploring the Design Space of Glanceable Feedback for Physical Activity Trackers, In Proceedings of Ubicomp’16. |

In her recently published work, Jordan Etkin asked individuals to count their steps over the course of a day. Not surprisingly, she found an increase in the number of steps taken as compared to the control condition, when individuals weren’t asked to count their steps. What was more interesting, was that step counting led to a reduction in people’s enjoyment of walking. Etkin argued that by invoking the metaphor of “measuring” and highlighting quantitative outcomes, attention is drawn away from the intrinsic joys of an activity towards external rewards (see Deci et al. 1999). Exercise is experienced a little more like work, which in turn may decrease the likelihood of continued engagement in one’s free time (as found in Etkin’s study).

In other words, instead of supporting people with construing exercise as an enjoyable and meaningful activity to guarantee prolonged engagement, activity trackers might establish mechanisms, which guarantee a short-term increase in physical activity at the risk of potentially detrimental long-term effects.

Of’course, this might be a rather narrow vision of these technologies. No doubt, self-quantification is the dominant narrative in marketing, and often in design. But richer narratives may be found if one looks at the ways in which users appropriate such technologies.

To inquire into this, we surveyed recent, memorable experiences people had with activity trackers, and tried to understand these in terms of need fulfilment, using a theoretical and methodological framework proposed by Sheldon et al., 2001. A factor analysis revealed a two-dimensional structure of users’ experience driven by the needs of physical thriving or relatedness. More than just supporting behavioral change, we found trackers to provide multiple psychological benefits, such as enhancing feelings of autonomy as people gained more control about their exercising regime, or experiencing relatedness, when family members purchased a tracker for relatives and joined them in their efforts towards a better, healthier self. Interestingly, we found that while numerical feedback lost its relevance over time, users continued to wear the tracker for a number of reasons, ranging from the perceived future value of data accumulation, to the mere symbolic empowerment that users felt when wearing the tool.

With multiple studies highlighting high abandonment rates of physical activity trackers, a question is raised as to how well they perform for different individuals. One meaningful framework to characterise diversity in populations is Prochanska’s et al. Transtheoretical model, also known as the stages of behaviour change [1]. TTM suggest five stages that people will typically go through when planning and implementing a behaviour change, such as quitting smoking, or increasing physical activity. These are: precontemplation (not ready), contemplation (getting ready), preparation, action and maintenance.

In our Habito study, we found the tracker to work best for people that are in the intermediary stages of behaviour change. Individuals in the contemplation and preparation stages, who have the intention but not yet the means (i.e. motivation, strategies) to change, had an adoption rate of 56% (with adoption being defined as use that extends beyond the first two weeks), whereas individuals in precontemplation, action or maintenance stages had an adoption rate of only 20%.

Yet, these individuals (in the intermediary stages of behavior change) are only about 43% of the population that are likely to purchase an activity tracker, or download an app on their smartphones (based on our sample). So, there is a significant population of users for whom we currently fail to address their needs.

To remediate this situation, we need to ask new questions, such as, how can trackers instill initial motivation for behavior change rather than merely supporting the process of it? Individuals in the precontemplation stage are often unaware of the extent of their inactivity. As a result, initial experiences are marked by dismay as individuals realize their low activity levels. Rather than confronting users with this “truth”, one could ask how trackers could increase individuals’ perceptions of self-efficacy and competence and support them in the gradual increase of physical activity.

A second challenge is detecting the stage of behavior change individuals are in from behavioral cues. In doing so, one should bear into account that transitions across stages are not always unidirectional. Individuals often relapse to prior stages of behavior change. When this occurs, some individuals “feel like failures – embarrassed, ashamed and guilty” [6]. Future work should thus embrace behavior change as a dynamic journey, should seek to understand the experiential side of behavior change, and to design strategies that support individuals across the full spectrum of their journey.

Together with Ruben Gouveia and Marc Hassenzahl, we received an Honorable Mention Award for Best Paper for the paper How Do We Engage With Activity Trackers? A Longitudinal Study of Habito. The Honorable Mention Award is given to a paper that was identified by the Program Committee as being among the top 5% of all submissions to UbiComp 2015. UbiComp is the premier interdisciplinary conference in the field of ubiquitous and pervasive computing, and a top-ranked international conference in computer science.

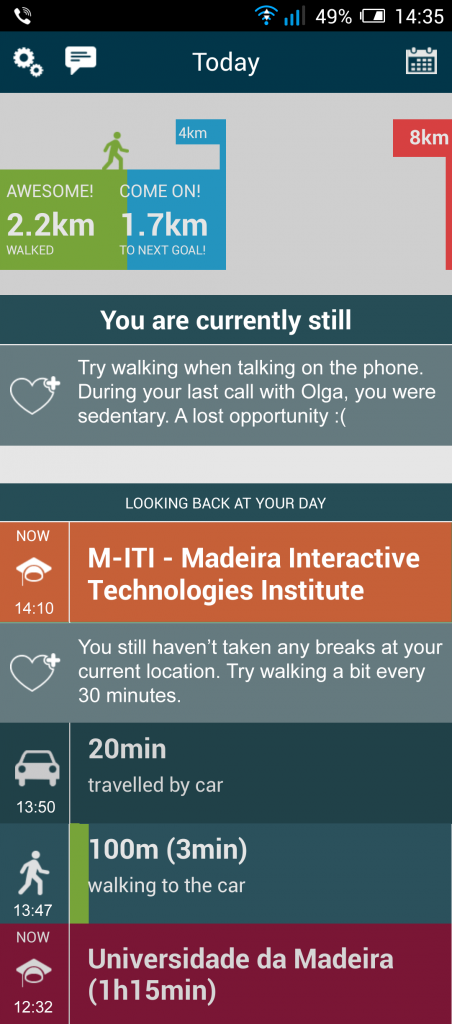

We report on a 10-month in-the-wild study of the adoption, engagement and discontinuation of an activity tracker called Habito, by a sample of 256 users who installed the tracker on their own volition. We found ‘readiness’ to behavior change to be a strong predictor of adoption (which ranged from 56% to 20%). Among adopters, only a third updated their daily goal, which in turn impacted their physical activity levels. The use of the tracker was dominated by glances – brief, 5-sec sessions where users called the app to check their current activity levels with no further interaction, while users displayed true lack of interest in historical data. Textual feedback proved highly effective in fueling further engagement with the tracker as well as inducing physical activity. We propose three directions for design: designing for different levels of ‘readiness’, designing for multilayered and playful goal setting, and designing for sustained engagement.

| Gouveia, R., Karapanos, E., Hassenzahl, M. (2015) How Do We Engage With Activity Trackers?: A Longitudinal Study of Habito. In Proceedings of Ubicomp’15 (pp. 1305-1316). ACM |

mHealth has undoubtedly made significant progress over the past decade. Yet, tools such as physical activity trackers are rather naive as fitness coaches: they can tell you how much you walk, but not what you can do to perform better.

In an ongoing project, we are trying to inquire into whether part of the intelligence of activity trackers can be crowdsourced. As an example, CrowdWalk is a mobile app that leverages the wisdom of the crowd to produce location-based “walking challenges”, and thus attempts to assist behavior change through highlighting opportunities for physical activity. CrowdWalk infers users’ location and presents a list of walking activities that can be initiated from one’s current location. For instance, as users enter a building CrowdWalk may suggest taking the stairs. When entering a supermarket, users may be challenged to leave their shopping cart behind while walking back and forth to gather shopping items.

With the design of CrowdWalk, we aim at fostering an alternative approach to the dominant narrative of quantification in health-promoting technologies.

As HCI shifts “to the wild”, in-situ methods such as Diary Methods and the Experience Sampling Method are gaining momentum. However, researchers have acknowledged the intrusiveness and lack of realism in these methods and have proposed solutions, notably through lightweight and rich media capture. In this paper we explore the concept of lifelogging as an alternative solution to these two challenges. We describe Footprint Tracker, a tool that allows the review of lifelogs with the aim to support recall and reflection over daily activities and experiences. In a field trial, we study how four different types of cues, namely visual, location, temporal and social context, trigger memories of recent events and associated emotions. We conclude with a number of implications for the design of lifelogging systems that support recall and reflection upon recent events as well as ones lying further in our past.

Technologies for behavior change have immense potential. Consider, for instance, the case of physical activity trackers. Our healthcare systems are facing unprecedented challenges. Western lifestyles, now spreading throughout the world, have had a direct impact on the increase of chronic diseases, which today account for nearly 40 percent of mortality cases and 75 percent of healthcare costs, and are predicted to increase in frequency by 42 percent by 2023. Obesity alone has been estimated to account for 12 percent of the health-spending growth in the U.S. It is thus no surprise that policy makers and political figures are increasingly calling for a healthcare model that stresses patient-driven prevention rather than cures, such as Hillary Clinton’s call for a health initiative that focuses on “wellness, not sickness” and Gordon Brown’s call for an “NHS [National Health Service] of the future [being] one of patient power, with patients engaged and taking control over their own health and healthcare.”

In this new landscape of healthcare, physical activity trackers have become a focus in both research and practice, as they can provide many benefits ranging from empowerment and people taking responsibility for their own health to opportunistic engagement in desired behaviors [1]. The market for wearable activity trackers such as Fitbit, Jawbone up, and Nike+ Fuelband has seen a rapid growth, estimated to have grossed $1.15 billion in 2014.

| Karapanos, E. (2015) Sustaining User Engagement with Behavior Change Tools, Interactions 22, 4 (June 2015), 48-52. |

Sustaining User Engagement Is Challenging

Despite significant recent advances, one could argue that research and practice in behavior-change technologies are still in their infancy. The industry is currently following a technology push paradigm, appealing to the user’s interest in experimenting with self-quantification. In research, our efforts are continually expanding to different sensor technologies and different uses of them, as if we have actually been successful in developing behavior change strategies that work.

The reality of behavior change technologies, however, is somewhat disappointing. A recent survey found that over a third of owners of commercial physical-activity trackers discarded them within six months [2]. The reality is even worse for activity-tracking mobile apps, where adoption is often more exploratory, and for researchers who typically deal with exploratory ideas and prototypes that are necessarily less developed than commercial products. For instance, in our own work we found that out of the 86 users who installed a physical activity tracker that we deployed on Google Play, only 21 percent of them kept using it for more than two weeks [3].

Ensuring long-term engagement with behavior-change tools is important for a number of reasons. The majority of today’s behavior-change technologies rely largely on the principle of self-monitoring—the idea that monitoring our behaviors makes us more likely to engage with behavior change, be it walking the extra steps, reducing our energy consumption, or other changes. Research has repeatedly shown, however, that individuals quickly relapse into their old habits once self-monitoring ceases.

Strategies for Sustaining User Engagement

The question we pose in our research is how to sustain user engagement with behavior-change technologies (and the behavior-change process per se) over a prolonged period of time. We now describe some of the different paths we have explored so far.

Creating checking habits. The question we are asking here is: How can we design behavior-change technologies that entice users to keep checking their data?

Recent work has highlighted the capacity of smartphones to create strong checking habits —“brief, repetitive inspection[s] of dynamic content quickly accessible on the device” [6]. Powered by instant information rewards found most commonly in social media updates and incoming emails, these brief interactions, lasting fewer than 15 seconds, have been found to account for as much as 40 percent of our usage sessions with smartphones.

On one hand, the potential for checking habits to transform into addictive behaviors is alarming. On the other hand, checking habits can also serve a good purpose—for instance, if they sustain user engagement with an application that helps them to exercise more.

Habito does this through the use of textual feedback. We created a total of 91 messages, which are displayed to users over time and when certain conditions are satisfied. Some of these messages aim to support further inferences about the activities performed. For instance, when the system has sensed high physical activity at a given location, it colors this entry as green, and the text below may provide further detail, for example: “M-ITI has been your most active location of the week. On average, 400m more than other locations” and “In your breaks at M-ITI, you walked an average of 50 meters.” Others provide mere facts, such as “Only 13% of children walk to school nowadays compared with 66% in 1970” or “Keep active. Simple movements such as fidgeting, which includes knee shaking or pen tapping, can burn up to 3,600 calories per day.” Others provide just-in-time recommendations such as “You have been sitting for 45 minutes. Try taking a break every 30 minutes,” when the system has sensed extended sedentary activity, or “If you have time, park your car further away and walk the remaining distance!” when the system has sensed commuting by car. Others try to create a sense of community, for example, “O’Calhau is the 2nd most physically active community in Funchal. Just 300 meters below the first (M-ITI).”

Our hypothesis was supported. We found that users take less time to come back to Habito following an interaction with a novel message compared with a message they had seen before. Furthermore, interacting with persuasive messages as opposed to merely informational messages would make them take a walk in a shorter period of time.

Social translucence. The second strategy suggests: If persuasive technologies are not successful in the long run, what if we push the responsibility to families and other strong social ties? This implies a change in perspective. Rather than thinking of such technologies as persuasive, we think of them as socially translucent, where the goal is to raise awareness of one another’s behaviors. Behavior change in this sense is expected to happen not as a result of the technology, but rather because of the often-ingenious forms of nudging families employ (e.g., a mother putting some tape over the light switch so her children don’t use it every time they come into the room).

While social influence is one of the most common approaches employed both by research prototypes and commercial products, it is often reduced to simplistic techniques (such as competition) that are mediated only through the technology. In our work we attempt to reduce the role of technology in the behavior-change process to two important attributes: visibility—allowing information about the individual’s behaviors to be seen by others—and mutual awareness—raising the individual’s awareness that this information is visible to others (“I know that you know”). The combination of these two attributes is expected to lead to compliance and feelings of accountability regarding one’s behaviors [7]. Most important, technology’s role is reduced to one of mediation; it is the communication and coordination practices that families establish that define the path to behavior change.

Consider for instance Social Toothbrush, a prototype developed by Ana Caraban as part of her master’s thesis (Figure 3). The prototype senses the frequency, duration, and performance of the user’s toothbrushing practices and provides information both in real time and during subsequent use, as does any other personal informatics tool. More important, a minimalistic glanceable display (in the form of a colored light in the lower part of the prototype) allows a person entering the bathroom to know whether the toothbrush has been used during the past couple of hours. Similarly, Donovan Costa in his master’s thesis developed Hydroscale, a prototype that senses the user’s water-intake practices in the workplace and reminds them when it’s time to have another sip. The fact that the display is visible to everyone in the vicinity plants the seeds for playful nudging and discussion over the user’s water intake. One may as well choose to adhere to recommended water-intake practices to avoid this form of nudging. This strategy certainly poses significant ethical questions: Is it likely to raise conflicts within families or between individuals, or is it the first step to the creation of norms and adherence to them, eventually even leading to a possible reduction in conflicts?

Supporting action. While today’s physical-activity trackers and behavior-change technologies all inform users about their levels of physical activity, they do little to assist them in implementing new habits. CrowdWalk tries to combat this by proposing walking activities one can do from the current location. Activities are produced by users and can be tied to breaks (e.g., “walk around the campus—it will take you 15 minutes”) to commuting (e.g., “walk downtown rather than taking the bus”) or to practices that involve walking (e.g., “try to maximize the distance walked while shopping in the supermarket”). While CrowdWalk proposes walking activities to users, it doesn’t nudge them to carry out these activities (see [8] for a different approach). While this avoids , it suffers from possible attrition as individuals forget or lose interest in the proposed activities. How to assist users in transforming these walking activities into daily habits is a key question for such tools.

Strategies for Sustaining User Engagement

We proposed three directions, but also considerations, for the design of behavior-change technologies that sustain users’ engagement.

The first direction implies that behavior-change technologies have to fight for users’ attention. In a life of constantly fragmented attention filled with distractions and changing priorities, how do we design technologies that do not overwhelm the user, and yet do not disappear in the muddle of daily life?

The second direction implies that social relationships may be more effective in inducing behavior change than human-technology ones. The question posed to us designers is how to integrate humans and technologies in supporting the behavior change process in a way that is ethical, effective, and socially acceptable.

The third direction implies that assisting behavior change is not only about reminding people, but also about telling them how. Keeping to a healthy diet is far easier when a clear, step-by-step process is available. As designers, we should ask, does the technology suggest clear actionable goals that are tailored to the user? Does the technology have the agency to stress the implications of these goals?

Last but not least, we suggest that engagement is key to behavior change. In fact, the majority of early studies on behavior-change technologies overlooked users’ engagement, focusing directly on the final outcome: whether behavior change took place or not. We argue that understanding how people engage with behavioral feedback is an important gateway to the invention of more effective behavior-change strategies. For instance, in a recent study we found that contrary to conventional wisdom that portrays behavior change as the result of deep knowledge about one’s own behaviors, users truly lack the interest to reflect on past behaviors. Instead, more than 70 percent of the long-term usage of our tracker related to glances—brief, five-second sessions where users called the app to check their current activity levels, with no further interaction [3]. Consequently, we should question the current paradigm of deep reflection underlying most of today’s technology. Instead, we should ask: How can we maximize the impact of these glances on individuals’ behaviors, and how can we leverage these glances to act as proxies for deeper engagement with the feedback?

Human behavior accounts for a significant chunk of domestic energy consumption. In fact, simple things like turning off the lights in empty rooms or setting the thermostat to 1-2°C lower during Winter can have quite an effect if they scale to a significant part of the population.

The question then raised is, can feedback around one’s energy consumption lead to behavior change? If true, it leads to a cost-effective solution to environmental sustainability, next to the more expensive and slow in implementation infrastructural changes. Researchers in environmental psychology and energy policy have studied this question for over 30 years. Studies have repeatedly highlighted that simple periodical feedback (such as in the form of a monthly energy bill) on the household’s overall energy consumption leads to 10-20% decrease in consumption.

In the field of HCI, we only recently became interested in energy feedback, and in particular the so-called eco-feedback technologies. Such technologies present an advancement to traditional feedback strategies through providing a) real-time feedback (e.g., rather than once per month), and b) disaggregate feedback (i.e., characterizing the consumption of each appliance, e.g., through Non-Intrusive Load Monitoring, rather than the aggregate consumption of the household).

For long, HCI had neglected longitudinal studies. As a result, our understanding of the qualities of interactive technologies was limited to users’ initial interactions. Learnability was emphasized over systems’ long-term usability. Aesthetics and novel interaction styles over the true value technologies brought to people in daily life.

With the emergence of the User Experience subfield, we set out to understand how much could early interactions differ from users’ prolonged engagement with technology.

In the first, exploratory study (Karapanos et al., 2008), we tested a popular structural model of UX (Hassenzahl’s pragmatic/hedonic framework) at two moments in users’ adoption of a technology: during the first week of use, and four weeks after.

In our second study (Karapanos et al., 2009) we conducted an in-depth, five-week ethnographic study where we followed 6 individuals during an actual purchase of the Apple iPhone, and found prolonged use to be motivated by different qualities than the ones that provided positive initial experiences. We crystallized these findings in the form of a framework that identifies three phases in the adoption of interactive technology – orientation, incorporation, and identification – and three forces of temporality – increasing familiarity, functional dependency, and emotional attachment.

| Karapanos, E., Hassenzahl, M., and Martens, J.B. (2008) User experience over time. In CHI ’08 Extended Abstracts on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI EA ’08). ACM, New York, NY, USA, 3561-3566. |