I intentionally chose a provocative title. Can we really design behaviour? Can technologies have such an influence on individuals’ behaviour that we can talk about “designing behaviour” through technology?

To a large extend, behaviour change technologies nowadays rest on the assumption that knowledge leads to behaviour change, an idea that is deeply rooted in the “quantified self” community. We assume, for instance, that making people aware of how much, when, and where, they walk (or don’t), will lead them to uncover patterns in their behaviours and take actions to increase their physical activity. Our research has revealed that this is not necessarily true, and that we often hold incorrect assumptions about how people use these technologies. For instance, our habito study, revealed that people rarely look back at their past performance data, and that only 30% of the users set their own walking goal.

Rather than thinking of such technologies as ones that enable deep reflection over one’s behavioural patterns, could we have more success if we focus on shaping the choice architecture at moments of decision making? Consider, for instance, the popular road sign stripes that are strategically positioned closer and closer together as we approach a steep curve, making us believe that we are over-speeding. Such a simple intervention has been found to decrease car accidents by 36%.

How could we transfer such approaches to the design of behaviour change technologies? I personally see two approaches. One is to infer when such critical moments of decision making happen – approaching the elevator, browsing through online food delivery options etc. A second is to provide persistent, glanceable feedback that keeps reminding people of their goal. Consider, for instance, that people glance at their smartwatches 80-150 times a day to check the time or incoming notifications. Might we leverage on this to present physical activity feedback at the periphery of their attention?

In our recent paper we explored just that. For the purpose of this blog article, I wanted to emphasize what we found with one of the prototypes we developed, TickTock.

Most activity trackers will tell you how much have you walked so far in the course of the day. This, of course, is routed in the idea that people set daily walking goals, and feedback serves to make them aware of their performance so they can meet their goal.

With TickTock, we tried to change the logic. TickTock will only tell you how active you were over the past hour. As a result, TickTock emphasises keeping a balance in your day, i.e. avoiding prolonged periods of sedentarism, which has been found to be a health risk factor independently of the amount of physical activity one performs over the course of a day.

What we found was rather astonishing, I think. I initially thought there must some error in the data. I asked Ruben to scrutinise the data collection script. He couldn’t find any error.

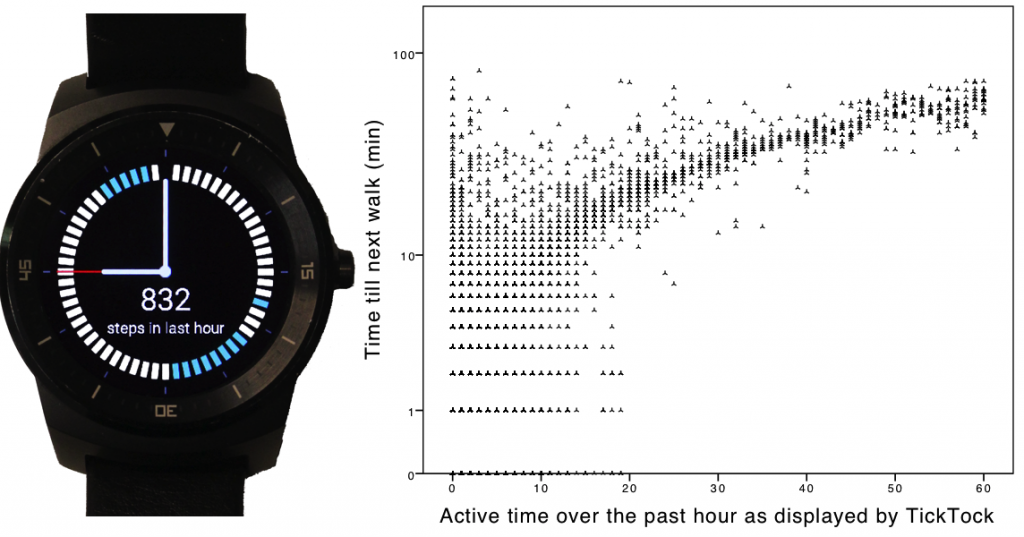

I turns out, TickTock had a profound impact on individual’s behaviours. We performed a linear regression analysis to predict the time people took till their next walk after checking the watch, based on the feedback they received, namely how active (o-60 mins) they were over the past hour. We found this single variable to account for 76% of the variance in the data! For every additional 10 min of physical activity that the participants saw they performed over the past hour, they would take an extra 9.5 min till their next walk. Participants who saw that they walked 10 or less min over the past hour had a 77% probability of starting a new walk in the next 5 min.

What do those findings suggest? First, that these technologies are far from neutral, they emphasise certain ways of living, and as designers, we should pay close attention to the assumptions embedded in our designs and to align feedback with the goal we want to achieve. Second, they highlight they surprising impact glanceable feedback has on individuals behaviours. The habito study highlighted that the dominant mode of use of physical activity trackers is glancing and it serves to support self-regulation of immediate behaviour. This study further demonstrated the power of glanceable feedback in shaping individual’s behaviours.

| Gouveia, R., Pereira, F., Karapanos, E., Munson, S., Hassenzahl, M. (2016) Exploring the Design Space of Glanceable Feedback for Physical Activity Trackers, In Proceedings of Ubicomp’16. |